最近、別のブログ記事で、あるお客様が「抹茶の苦味をもっと美味しくする方法はありますか?」と質問されました。そのお客様は、ワイン用のメルローのような特定の品種である宇治ひかり抹茶について言及していました。

簡単で素早い答えは、ミルクと砂糖を加えて、どんな高品質の抹茶でも甘くてクリーミーなラテにすることです。

より微妙な答えは、適切な温度(70〜80℃/160〜175°F)で適切な水(軟水)を使用することです。

しかし、良質の抹茶の風味とその風味がどのように実現されるかについては、理解しておくべきことがいくつかあります。

風味を考える上で、特定の品種は最後に考慮すべき事項です。品種については後ほど改めてご説明します。

特定の茶道の流派が推進する特定の人生哲学(別のブログ投稿のテーマ)はさておき、日本の抹茶業界では、抹茶の品質を決定する際に一般的に次の点を考慮します。

- 風味:うま味が高く、苦味と渋みが少ない。

- 滑らかな口当たり(粒度が小さい)。良質な「儀式用」抹茶は5ミクロン程度の粒度で、口の中でざらざらとした感じがしません。料理用の抹茶は一般的に15ミクロンで、ざらざらとした感じがします。海外産の「抹茶」の中には25ミクロンもの粒度のものもあると聞きます。

- 鮮やかな緑色の粉、濃い緑色の抹茶色

- 豊かな香り

- 泡や泡立ちは、実は日本ではあまり考慮されていません。これは主に裏千家茶道流派(日本国外で圧倒的に最大規模、最も国際的、したがって最も影響力のある流派)が求める特徴だからです。しかし、私たちの目的としては、きめ細かな泡立ちでクリーミーさを増すことが簡単にできるものが高品質の結果であるはずです。

栽培技術

施肥、遮光、カテキン、テアニン

茶葉には数千もの風味成分が含まれていますが、大きく分けて2つのグループに分けられます。抹茶の苦味を生み出すカテキン(抗酸化物質)と、うま味を生み出すアミノ酸であるL-テアニンです。茶葉は成長し、日光にさらされるにつれてテアニンを失い、カテキンを生成します。抹茶の葉は日陰で育てられます。これは、うま味を高め、苦味を抑えるためです(苦味は、本来の健康効果よりも劣ります)。

高級抹茶の茶葉を栽培する農家は、風味を最大限に引き出すために、主に窒素を主体とした肥料を畑に施します。有機栽培抹茶の大きな問題は、肥料を多く施した茶葉(つまり、美味しく栄養豊富な茶葉)に集まる虫の被害を避けるため、肥料の量が少なくなってしまうことです。一方、農薬に頼っている畑では、茶葉に集まる虫を農薬で駆除できるため、肥料を多く施すことで、より豊かな茶葉を生産することができます。

遮光には、主に2つの種類があります。キャノピーシェーディングとプラスチックを使った直接遮光です。キャノピーシェーディングでは、植物が自由に成長できるため、葉を収穫するには手間のかかる手摘み作業が必要です。最高品質の葉を作る農家は、この作業を行い、年間を通して手作業で畑を管理することで、受賞歴のある葉を生産しています。例えば、春の新葉が芽吹く前に、農家は各枝の頂点の芽を摘み取ります。これは、既存の基部葉の上に新しい芽が横方向に成長するようにするためです。これらの新しい芽は、抹茶と碾茶の両方において最高品質の葉となります。

画像(左から):従来の天蓋遮光(ゆのみの生産パートナーの契約茶園)、プラスチック製遮光材を使用した天蓋遮光(西出製茶所の提携茶園)、プラスチック製遮光材を使用した直接遮光(おぶぶ茶園)

非常に伝統的な樹冠シェーディングでは、何らかのわら素材を 4 週間かけて徐々に重ねて、葉が成長するにつれて通過する日光の量を減らし、農家が日光の量を非常に微妙に調整できるようにします。

機械による収穫は、はるかに効率的であるだけでなく、畑から生垣を形成し、植物に直接日よけを掛けやすい形状を作ることができます。キャノピーシェーディングよりもはるかに簡単ですが、葉への圧力と、葉がバタバタと当たって傷む可能性が高く、葉の品質が低下します。

最後に、遮光期間の長さも葉の品質向上に貢献し、カテキン含有量を減らしてテアニン含有量を維持します。しかし、葉の成長を阻害し、収穫量の低下と価格上昇につながります。遮光期間の一般的な長さは4週間とされていますが、品質の低い葉の場合は最短14日間、高品質の葉の場合は最長40日間の遮光期間となる場合があります。

ここで、栽培には品質に影響を与える可能性のある他の要因があることを指摘しておきますが、これは別の議論のために残しておきます。収穫までの数か月と数週間の天候、気候、土壌、地域などです。

収穫の季節

春の収穫時期は、葉に最も多くの栄養分が含まれており、最も風味がよくなります。適切に日陰に当てられていれば濃厚でクリーミー、そうでない場合はより苦味が増します。実際、日本では、日陰に当てられていない葉を挽いて、抗酸化物質が豊富な緑茶パウダーを作ります(日陰に当てられた葉から作られていないため、日本では抹茶とは呼ばれません)。抹茶は他の収穫時期でも作られますが、葉がより長く成長してより大きなサイズで収穫されるため、収穫量が増え、より苦味が増す傾向があります。春と同じサイズで収穫すると、収穫量が少なくなるだけでなく、葉はそれほど栄養分が豊富ではないため、風味も弱くなります。日本では、夏と秋に収穫された葉は一般的に料理用の抹茶に使用されます。しかし、明確な基準がないため、特に日本国外では、悪質な販売者や知識のない販売者が、日本では受け入れられないような抹茶でも「儀式用」として販売することがあります。

研削

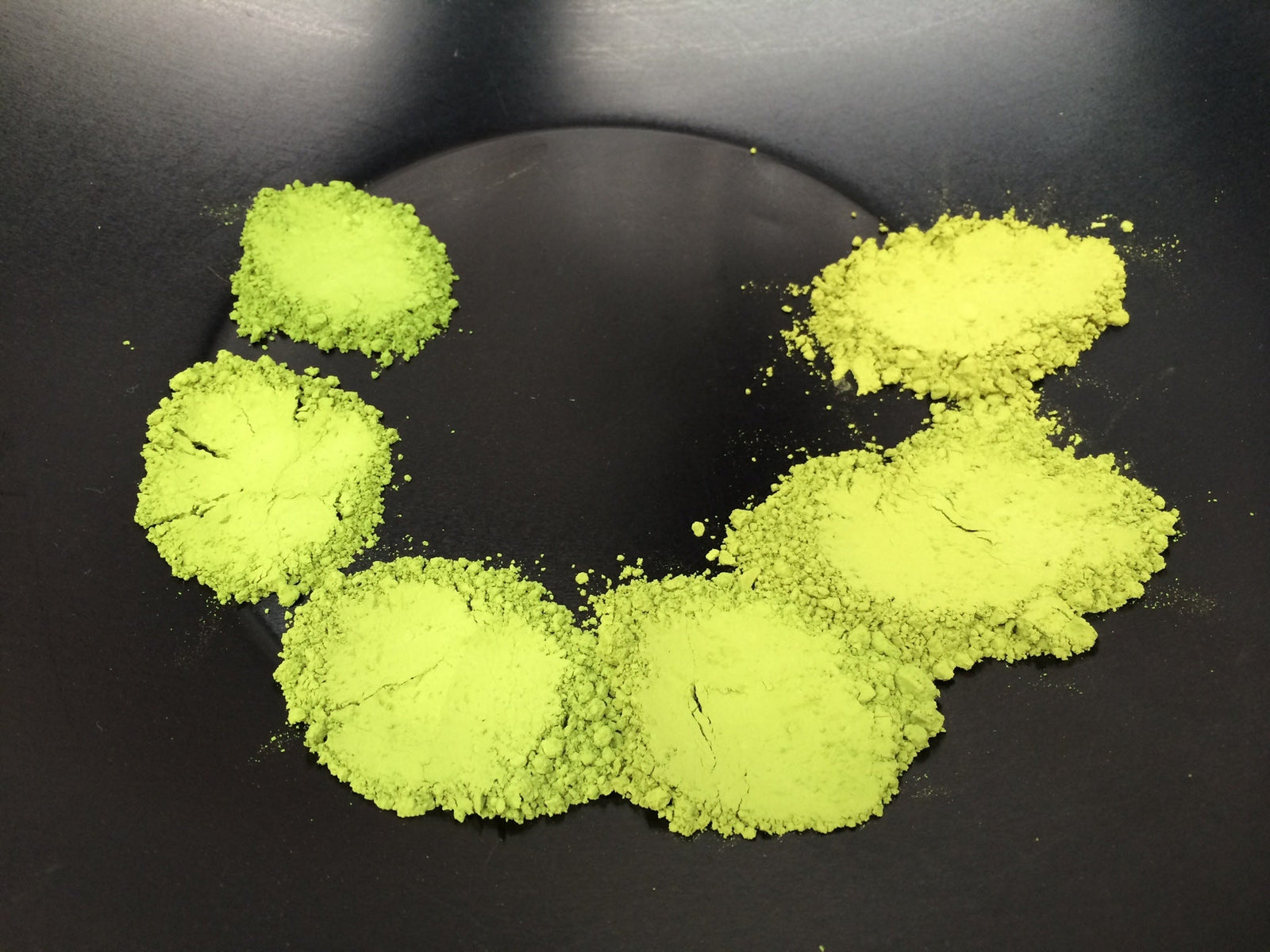

松玉園の碾茶品種試飲セット 風味、色、香りの質を左右するもう一つの要素は、茶葉を抹茶に挽く方法です。最初の工程は、生の茶葉を乾燥させ、抹茶に挽くことです。この乾燥させた茶葉は伝統的に碾茶と呼ばれ、基本的には収穫したばかりの薄葉を蒸し、専用の炉で網の上で乾燥させることで作られます。その後、もろい茶葉は粉砕されてフレーク状にされ、この過程で茎と葉脈が選別されます。このフレーク状の碾茶を、抹茶に挽くことができます。

風味、色、香りの質を左右するもう一つの要素は、茶葉を抹茶に挽く方法です。最初の工程は、生の茶葉を乾燥させ、抹茶に挽くことです。この乾燥させた茶葉は伝統的に碾茶と呼ばれ、基本的には収穫したばかりの薄葉を蒸し、専用の炉で網の上で乾燥させることで作られます。その後、もろい茶葉は粉砕されてフレーク状にされ、この過程で茎と葉脈が選別されます。このフレーク状の碾茶を、抹茶に挽くことができます。

しかし、専用の窯を持たない加工業者は、標準的な煎茶揉み機を用いて、高速乾燥と緩揉みを組み合わせた乾燥茶葉を製造することに成功しました。この乾燥茶葉は「もが茶」と呼ばれ、粗挽きの抹茶に加工されます。この方法は大量生産が可能で、品質の低い抹茶にも使用できるため、従来の製法よりも効率的に大量生産が可能です。

最後に、粉砕は伝統的な石臼(碾茶挽き専用の溝が刻まれた30kgの石臼にモーターを接続して自動化したもの)または粉砕機(セラミックボールミルまたはジェットエアー粉砕機)で行います。石臼の工程は一般的に時間がかかり、1日10時間作業しても500g未満しか生産できず、最も細かい粒度の茶葉が得られます。工場では回転速度を上げて、より大量の茶葉をより早く、より粗い粒度の茶葉を生産することもできますが、より大容量の粉砕機が利用できるようになった今、そうする理由はほとんどありません。

同様に、これらの粉砕機は、処理量が多い(1台1日あたり20~100kg)ため、一般的に低品質の抹茶に使用されますが、必要に応じて石臼レベルの1~5ミクロンの粒度にすることも可能です。しかし、碾茶の葉は全く同じで、機械の冷却システムの進歩にもかかわらず、石臼の方が抹茶の色と香りをより良く保つことができます。

ストレージ

風味、色、香りの品質に影響を与えるもう一つの要因は保管です。茶葉の収穫年よりも、挽いてからの抹茶の年数が重要な場合が多くあります。実際、最高級の茶葉はカテキンを分解するために6~12か月熟成されます。しかし、粉末に挽いた抹茶は風味、色、香りが急速に失われます。適切に密閉された専用の冷蔵保存をしたとしても、並べて比較すると6か月後には色と香りの違いに気づくでしょう(そのため、最高級の抹茶の賞味期限は6か月であることが多いです)。12か月の賞味期限が標準ですが、それでも製造業者は顧客が適切に保管していると想定していますが、多くの顧客は温度管理のない倉庫を使用しており、夏場は高温になる可能性があります。これが品質低下の大きな原因です。

栽培品種

特定の品種は品質に影響を与える最も微妙な要因ですが、他のすべての要因をコントロールできれば、比較試飲によって明らかな違いが明らかになります。同じ農家であっても、異なる圃場で異なる品種を栽培し、それぞれの圃場は異なる環境要因にさらされている可能性があるため、他のすべての要因をコントロールすることは非常に困難です。しかし、こうした点を考慮すると、同じ農家が生産した抹茶の品種を比較すると、違いが分かります。

やぶきたは、日本で栽培される茶葉の75%を占めるため、抹茶によく使われます。やぶきたは丈夫な植物で、良質な煎茶を生み出すことから、業界の標準となっています。しかし、葉に含まれるテアニンの量が少なく、うま味も少なく、緑色も鈍いです。下の写真はあずま茶園の写真です。

右から左へ:奥深緑(「深い緑」)、早緑(「早緑」- 若葉の緑)、やぶきた(「林の北」- 元々の植物が栽培されていた場所にちなんで名付けられた)

抹茶に用いられる品種の例は以下の通りです。これらはやぶきたよりも色が鮮やかだったり、旨味が豊かだったりすることが多いです。しかし、複数の品種を栽培する理由は、最終製品だけにとどまりません。農家が複数の品種を栽培することで病害虫のリスクを管理したり、品種によって収穫時期が異なるため、収穫時期をずらしたりするためです。それでも、抹茶に深く関心を持つ人にとって、異なる品種を比較できることは非常に興味深いことです。

オプション: あずま茶園の品種比較セット、おぶぶ茶園の品種比較セット。

- 朝日

- アサノカ

- 五光(または五光)

- 芳春

- 金谷みどり

- さみどり

- さえみどり

- 奥緑

- 奥豊

- 晴明

- 天明

- 宇治光

- 宇治みどり

2件のコメント

A very clear and comprehensive intro to Matcha. Thank You

Super interesting, thank you for sharing ! I am a wine nerd, so this is really similar to wine for me.